African-American artist Dox Thrash is in the spotlight on s3e60 of Platemark. Podcast host Ann Shafer speaks with Ron Rumford, director of Dolan/Maxwell, a private gallery in Philadelphia, which has a particular specialty in the prints of Stanley...

African-American artist Dox Thrash is in the spotlight on s3e60 of Platemark. Podcast host Ann Shafer speaks with Ron Rumford, director of Dolan/Maxwell, a private gallery in Philadelphia, which has a particular specialty in the prints of Stanley William Hayter and the associated artists of Atelier 17, as well as Black artists of the same era, such as Dox Thrash, Bob Blackburn, Norma Morgan, Elizabeth Catlett, Ed Clark, and more. Ron was eager to highlight an exhibition focused on Dox Thrash, which is on view at the African American Museum of Philadelphia through August 4, 2024.

They talk about Thrash and his invention of the carborundum mezzotint, Bob Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop and its relationship to Atelier 17 and Hayter, the monumental importance of the WPA printmaking division, and Ballinglen, an artist residency and gallery founded by Peter Maxwell and Margo Dolan in Ballycastle, a tiny farming town in County Mayo, Ireland.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Sunday Morning, c. 1939. Etching. Sheet: 12 5/8 x 10 5/8 in.; plate: 8 7/8 x 7 7/8 in. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

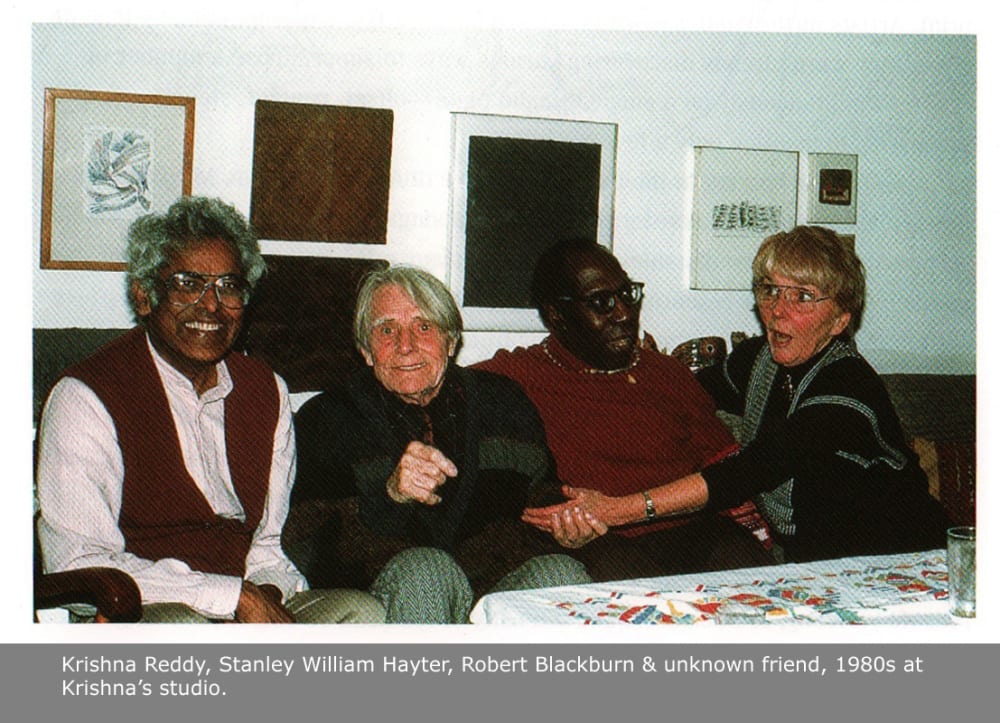

L-R: Krishna Reddy, Stanley William Hayter, Robert Blackburn, and friend, 1980s, at Reddy’s studio.

Hayter at the press with lithography press behind him, Atelier 17 in New York.

Photo of Pennerton West with fellow artists including Augusta Savage and Norman Lewis.

Pennerton West (American, 1913–1965). Troll in the Grain, 1952. State proof; color etching and lithography. Image: 14 ¾ x 17 ¾ in. Dolan/Maxwell Gallery, Philadelphia.

Pennerton West (American, 1913–1965). Troll in the Grain, 1952. State proof; color etching and lithography. Image: 14 ¾ x 17 ¾ in. Dolan/Maxwell Gallery, Philadelphia.

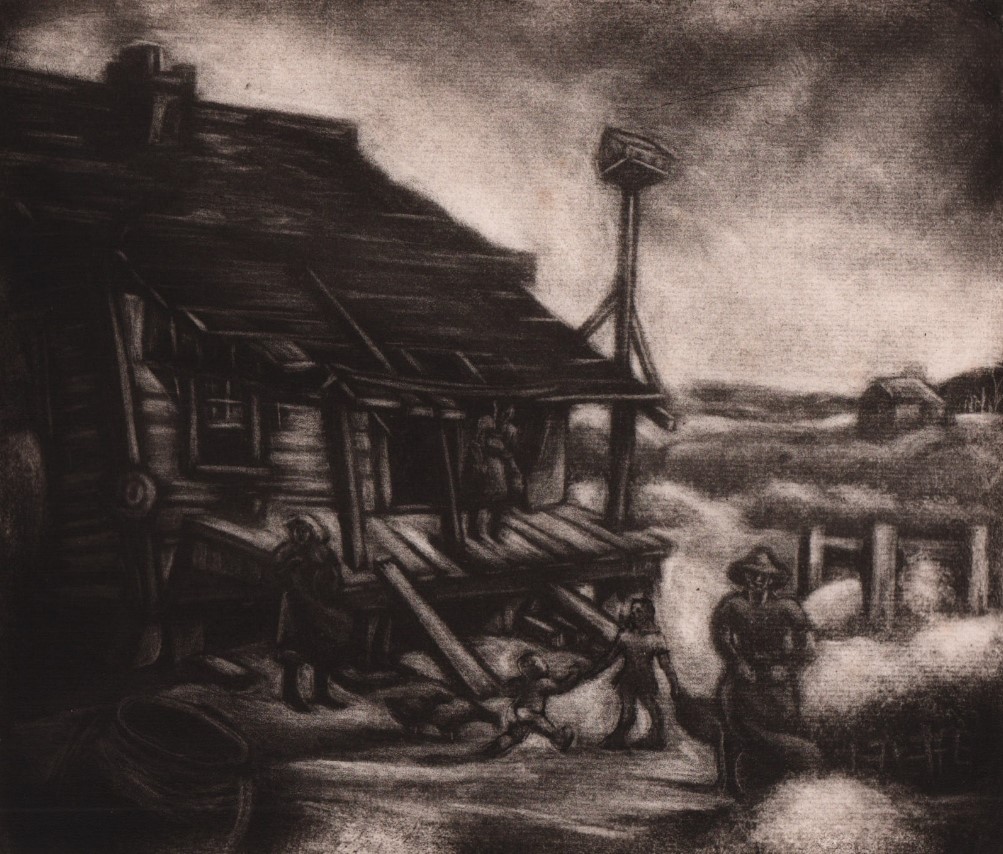

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Georgia Cotton Crop, c. 1944–45. Carborundum mezzotint. Plate: 8 7/16 x 9 7/8 in.; sheet: 11 ¼ x 11 3/4. in. Dolan/Maxwell Gallery, Philadelphia.

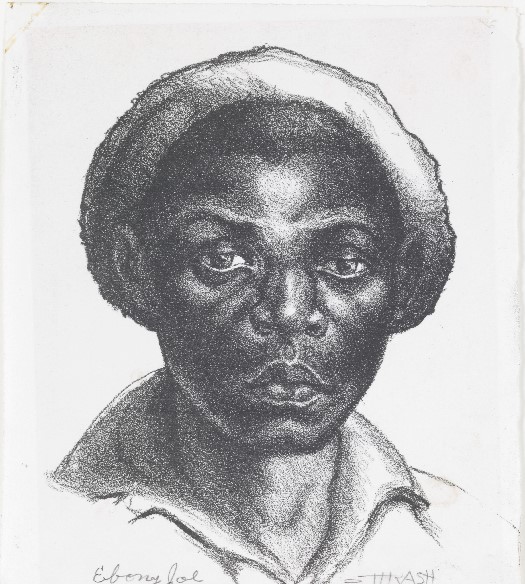

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Ebony Joe, c. 1939. Lithograph. Sheet: 10 5/8 x 8 7/8 in. Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Octoroon (Study for a Lithograph), c. 1939. Brush and ink wash over graphite. Sheet: 16 7/8 x 12 ¼ in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Octoroon, c. 1939. Lithograph. Sheet: 22 13/16 x 11 9/16 in. Collection of John Warren, Philadelphia.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). Charlot, c. 1938–39. Carborundum mezzotint. Plate: 8 15/16 x 6 15/16 in. Dolan/Maxwell, Philadelphia.

Michael Gallagher (American, 1895–1965). Lackawanna Valley, 1938. Carborundum mezzotint. Plate: 7 3/8 x 12 11/16 in.; sheet: 9 3/8 x 14 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

Hugh Mesibov (American, 1916–2016). Homeless, 1938. Carborundum mezzotint. Plate: 5 3/8 x 10 3/8 in. Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

Dox Thrash (American, 1893–1965). One Horse Farmer, c. 1944–48. Carborundum mezzotint. 9 x 6 in. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

John Ruskin (British, 1819–1900). The Garden of San Miniato near Florence, 1845. Watercolor and pen and black ink, heightened with whie gouache, over graphite. Sheet: 13 7/16 x 19 3/8 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

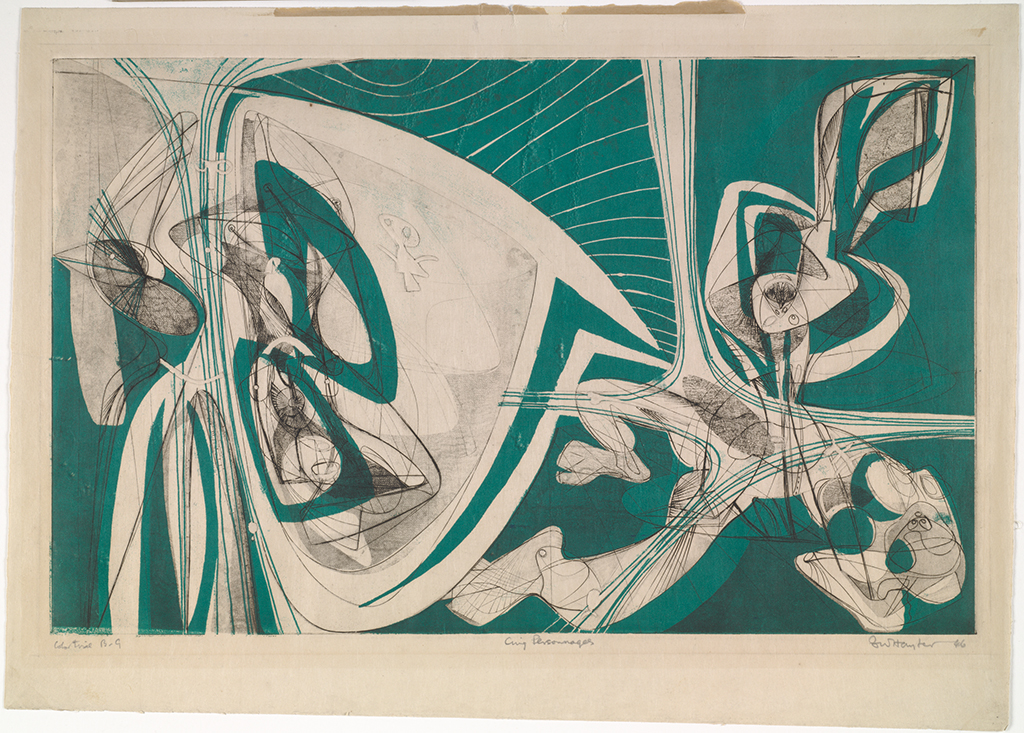

Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988). Cinq personnages, 1946. Engraving, softground etching, and scorper; printed in black (intaglio). Sheet: 495 x 647 mm. (19 1/2 x 25 1/2 in.); plate: 376 x 605 mm. (14 13/16 x 23 13/16 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore.

Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988). Cinq personnages, 1946. Engraving, softground etching, and scorper; printed in black (intaglio), and green (screen, relief). Sheet: 460 x 660 mm. (18 1/8 x 26 in.); plate: 376 x 605 mm. (14 13/16 x 23 13/16 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore.

Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988). Cinq personnages, 1946. Engraving and softground etching; printed in black (intaglio), orange (screen, relief), and purple (screen, relief). Sheet: 510 x 666 mm. (20 1/16 x 26 1/4 in.); plate: 376 x 605 mm. (14 13/16 x 23 13/16 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore.

Stanley William Hayter (English, 1901–1988). Cinq personnages, 1946. Engraving, softground etching, and scorper; printed in black (intaglio), green (screen, relief), orange (screen, relief), and purple (screen, relief). Sheet: 488 x 668 mm. (19 3/16 x 26 5/16 in.); plate: 376 x 605 mm. (14 13/16 x 23 13/16 in.). Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore.

Ballinglen Arts Foundation, Ballycastle, County Mayo, Ireland.

USEFUL LINKS

Imprint: Dox Thrash, Black Life, and American Culture. African American Museum in Philadelphia, March 23–August 4, 2024.

https://www.aampmuseum.org/current-exhibitions.html

John Ittmann. Dox Thrash: An African American Master Printmaker Rediscovered. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001. https://archive.org/details/doxthrashafrican00ittm

Dox Thrash House, Philadelphia: https://doxthrashhouse.wordpress.com/

Ballinglen Arts Foundation: https://www.ballinglenartsfoundation.org/fellowship/

Dolan/Maxwell’s IG: @dolan.maxwell

Ron’s IG account: @ron.rumford

Ron’s artist website: www.ronrumford.com

Platemark is produced by Ann Shafer

Theme music: Michael Diamond

Audio mixing: Dan Fury, Extension Audio

PR and Marketing: Elizabeth Berger, EYB Creates

You are listening to Platemark with me, Ann Shafer. Platemark is a podcast about a particular niche in the art world, that of prints and the printmaking ecosystem. We're talking about fine art prints, usually limited editions, etchings, lithographs, screenprints, relief prints. In series three, I will introduce you to artists, printers, publishers, gallerists, curators, art historians, and conservators in order to demystify this rarefied world and show you that we are all just people albeit with some really cool jobs. Today's guest is a dealer. His name is Ron Rumford and he is the director of Dolan Maxwell, a private gallery in Philadelphia. I've known Ron for a long time. He represents the Hayter estate. You've heard me talk about Stanley William Hayter before, one of my special loves. And so we've, we've known each other for a long time, but today he wants to talk to us about the artist Dox Thrash.

Now Dox Trash was a Philadelphia artist, a Black artist and printmaker who worked for the WPA early on in the 1930s and who developed a technique called carborundum mezzotint. There is an exhibition up as this episode is being released, it is on view until August 4th, 2024, at the African-American Museum in Philadelphia. The exhibition is called Imprint: Dox Thrash, Black Life and American Culture. It is a unique opportunity. There's about 100 works in the show 90 of which are by Dox Trash, and you don't find Dox Thrash's work often. You have to dig for it pretty hard. So this is a really, really wonderful opportunity. And anyone who's anywhere near Philadelphia ought to get in the car or on the subway or however else, and get thee to the African-American Museum.

Let's see. Housekeeping. I identify as a cis-het white woman, and I use the pronouns she/her. I record Platemark in Baltimore, Maryland, the land of the Piscataway Conoy people. Images that Ron and I talk about will be on the show notes at platemarkpodcast.com. Think about how much you appreciate the content that we're producing at Platemark, and head over to the website platemarkpodcast.com and hit support and donate. Become a monthly supporter at $5 a month. Or, leave a one-time donation of your choosing.

It's really just me doing this work. And, while I feel super, super, super passionate about it, as you know, I call myself the print evangelist, it is a lot of work and your support would be most appreciated. All right. I think that's it. Let's get rolling.

Ron, it's wonderful to see you. Thanks for coming on Platemark today. I'm happy to be here. Yeah, we've known each other a long time and have worked on various projects together, but I wanted to talk to you about one specific project that is live and ongoing at the moment. But before we do, can you introduce yourself for the listeners?

Okay, I'm Ron Rumford. I am based in Philadelphia. I am director of Dolan Maxwell, a art on paper focused gallery that is celebrating its 40th year. We opened in 1984, which seems impossible, but here we are. And I've been with Dolan Maxwell for almost 39 of those years. So, I've got a long, long history. I have a degree in painting, I studied painting, I didn't know what a print was when I was in college.

Early on, working at Dolan Maxwell, I became part of a very print centric point of view, uh, for the world. And I still maintain my own studio practice, which is mostly on paper and mostly printmaking. What else can I say? Dolan Maxwell has been part of the IFPDA since its inception. We had big gallery spaces in Philadelphia and New York. And we gave those up by 1991. We became private dealers, and our focus is on doing, uh, art fairs and shows around this country. And that seems to be a much better way to, as I say, get art in front of people, get eyeballs on the art, uh, because that is what the job is.

And even though we're told that everybody's going to not need to do that, and people don't always do that, but I still feel it's, I mean, the artist makes the thing for us to look at, not to have transposed through a screen someplace. I'm a bit, I'm a bit old school. Yeah. I think we agree on that one. Yeah.

The thing that's unusual about Dolan Maxwell in my mind, and I'm sure there are other galleries that do this, like Mary Ryan, I guess would be another good example, but you, you deal with older material and contemporary material, which I think is kind of a interesting balance. Do you feel better in one spot or the other?

I'd say it's a pendulum like everything, things change. I'd say over the past five years, it's a little bit hard to gauge any of this, it's swung more toward Modern and a lot of our projects have been Modern. We've just launched online an exhibition devoted to, uh, Robert Blackburn, who famously created a printmaking workshop in New York and interacted with hundreds and hundreds of artists from all over the world. Um, so Bob Blackburn died roughly 20 years ago. Um, to me, that's still contemporary. And, uh, we expanded to, and to try to show some of the range of his involvement with artists. So, uh, that goes back to artists who made prints with him as early as the 50s and up through the present and the artists that are still active and practicing today but benefited enormously from their interaction at the Bob Blackburn Printmaking Workshop. Yeah, I think Bob Blackburn Printmaking Workshop needs another big show. Well, a big show. Needs a big show. Yeah. I would love to see that happen.

I know me too. I don't think I could do it. Uh, once we started doing, and it's on our website now, but you've seen once we started doing it, uh, it just kind of grew and grew getting bigger. It expanded all by itself. It's been up for maybe a week now and or two weeks. And I keep thinking, Oh, we, I should have talked to so and so I should have talked to.

And, and so there's a rich mind to be explored of information and artists who were connected to Bob Blackburn. Well, yeah, he's interesting cause the parallels between him and Hayter are pretty, uh, pretty great because Blackburn has his own body of work, but there's all of those artists that he influenced and all that.

So it's like this kind of parallel thing. It's a great story. Oh, absolutely. And, and, uh, you know, we, we, we made Hayter and certain, certainly Krishna Reddy because Krishna Reddy is kind of shared by both of those artists. They were very close, all three of them. In fact, there's one picture where there's Krishna and ?Hayter and Blackburn sitting on a couch with a woman who we can't figure out who the woman is, um, but anyway. There they are and when they admired and esteemed one another in a, in a very big way. And so I was so glad to have an image that captured them just hanging out at a party at Krishna's loft. ?I feel like I was just talking to somebody who was trying to prove that Hayter and Blackburn had, had met slash I always believed worked together on something, you know, in some way.

And, um, uh, oh, now we need that photographic evidence. Sweet. Oh, they definitely knew one another. And, it's in the online exhibition, but, but Blackburn went to Paris around 53, I want to say. And, by chance, met Krishna then, and Krishna would have been very much involved with Atelier 17 at that moment.

I mean, I don't think we've uncovered any evidence, and unfortunately Bob's no longer around to ask, but I kind of can't imagine that he didn't at least. Well, he must have been aware of Atelier 17, if he didn't actually go and make things. And no one's identified anything that he actually made in Paris.

He went there and wanted to work with, uh, Desjoubert, the great lithography house in Paris. But he became frustrated because they were very conventionally organized and the artist did whatever drawing and designing and then the actual making of the prints was very separate. And, and Bob was already a master lithographer, so I think he thought, Oh, this isn't any fun.

I want to mess around. I want to, I want to touch the stones. I want to, you know, muck about. So he ended up traveling and having a great time. He, he reconnected with Beauford Delaney and Riva Helfond visited him while they were there. And they got a motorcycle and tooled around the countryside. So I think it was a wonderful time.

But I, I kind of wonder, it seems like he would have met Hayter then, but he certainly knew him in the 60s. And, and, and must have been, actually must have also been aware of the workshop because Blackburn's really starts making his own lithographs in 1948. And, Atelier 17 is still very active in New York at that time.

So, yeah, I always thought that there was some connection. I mean, this is an apocryphal story maybe, and I can't substantiate it right now, but I feel like you or somebody told me that Hayter helped Blackburn set up the studio initially in 48 or whenever Blackburn studio opened. Gosh, uh, there is a bit.

I think after Hayter went back to Paris, somebody from, from Hayter's set up an etching press at Blackburn Studios. So there's a very direct transfer of sharing equipment, sharing the knowledge that goes into operating an etching press versus litho presses, which is of course what Blackburn is probably best known for.

And I don't know if, um, I have to wonder, Bob Blackburn did so much with lithography, learning from Will Barnett, and then active, very actively collaborating with Will Barnett at his own workshop. And he says litho is my first love and etching is my second love. We have a quote of that, uh, that we found.

So yeah, there must have been great awareness. And I want to say somebody like, I think it's Harry Hoehn, an artist very close to Hayter, shared a loft with, Bob Blackburn. So I, I think the, between the two, it's very, very porous. I think everybody kind of knows everybody.

It's a, it's a pretty small scene at that point. If only they had all had iPhones and were taking pictures all the time, like we are. I know, I know. Although, there are some. I was looking at Christina Weyl's website recently. And she shared pictures of a party where Hayter is in New York and Sue Fuller is there and Bob Blackburn and probably Krishna.

So, you know, they're, they're all, they're all kind of in the same club and, and they hang out when they're able to. They reunite and, and I think really admired and, and loved each other. And, uh, that's, that's pretty nice. When I recently gave a talk in Asheville on Hayter, I, there was a picture, a photograph I showed of the studio and Phil Sanders pointed out to me that there was a litho press in the background of the studio shot, which will have. Shocking.

It is shocking. And he's like, do you, were they doing litho? I said, well, he wasn't opposed to it, but I'm, I wondered if the litho press was already in that space when they got the space and it was just a table. You know what I mean? Yeah. Well there are two locations, so it depends. I'll have to go back and find it.

?The later, yeah. Yeah. And, we have included in, in the online exhibition, uh, a pair of state proofs by an artist named Pennerton West and they're litho and etching. Oh! And I, I said, gee, what? And, and Christina said, oh, she probably just did the litho part of Blackburn's. Oh, gosh.

And in doing the research for the online exhibition, we came up with this photograph of a group of artists who are, you know, involved with the Harlem Community Arts Center. There's a single white woman and, and the caption says it's Pemberton West. Oh. And I thought, oh, hold on, that's gotta be Pennerton West.

And her name is often ?mishandled. So, uh, and I sent it to Christina instantly and she said, my gosh, it must be her. And I never thought that she would have been involved with the WPA. So going back and digging around, um, as we're doing right now, uh, it's always interesting. And there's, there's more out there if you know enough to get it that somebody's name's wrong, somebody's misidentified.

Uh, but anyway, but it was exciting. That is, yeah. Talking about Bob Blackburn. Uh, Bob Blackburn is what we consider, um, a Master Printer. He excelled in any technique that he approached. And since we're meant to talk about Dox Thrash, I can say Dox Thrash was also a Master Printer. He acquired the skill and expertise to excel at every technique that he would approach, which enabled him to help other artists find their way.

And of course he invents a technique while working for the WPA. He's born in Griffin, Georgia in 1893. Left Griffin, Georgia, to go to Chicago. I guess maybe it's about 10 years he's in Chicago, and is able to enroll, uh, in night's classes at the Art Institute. Wasn't that following his service in World War I? Did I dream that? Well, he starts before World War I. Oh, got it. And then he, and then he's pulled in and, and he's a Buffalo Soldier. He goes to France and serves and he was gassed at the very end of the war, a mustard gas injury.

So coming back to Chicago, he continued at the Art Institute. There's a whole list of jobs that he did, vaudeville, porter on a train, uh, elevator operator. There's all these jobs that he does to keep himself going. But so, wait, before we go any farther, so we were talking about Blackburn, now we're talking about Dox Thrash, another Philadelphia, well, Blackburn wasn't Philadelphia, sorry.

Dox Thrash is a Philadelphia artist, a black artist, who you have been carrying for a long time. I don't know if you're working with an estate of any kind, but you have, you have repped him in many, many fairs that I have seen and there's an exhibition up that you have been contributing to, right?

Yes. Where's the show? It's called Imprint Dox Thrash, Black Life, and American Culture. And it's an exhibition at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. Um, it's very hard to see that logo, but there it is. It's an exhibition that we talked about in 2017.

Something like that. And I began gathering works and organizing the exhibition then. We had other venues lined up. So, it it first went to the Palmer Museum of Art at Penn State University. It went to the Art Museum at Syracuse University. Then it also went to the Fort Wayne Museum of Art.

And somewhere along the way somebody suggested that we contact the Hyde Collection in upstate New York and then they took it. Then it got stranded there at the outbreak of COVID. They had to shut it down. So it was on the walls and they said, sorry, we have to close and it's safe. And it stayed there until the museum was able to open maybe an extra few months, in the dark, which was sad.

But that meant that the homecoming to Philadelphia was delayed, and I want to say four different times we talked about dates, where they hope to squeeze it in. Then as the complications of the pandemic lingered, it got pushed up, and then commitments that they had made to living artists, came, you know, suddenly they got there, the time rolled along, the calendar turned. So finally, finally, we have it now, and it opened, uh, a little over a month ago, And it is I think almost a hundred works.

At least 90 by Thrash and it's up until August 4th. Yeah. So hopefully I can't guarantee I'm going to get this episode out by then, but we're going to try. So, sorry, folks. I would appreciate that. It seems to be reaching people through our promotions.

I've had at least two or three different curators that I know who have come into town specifically to see it. Because it is a rare opportunity. Uh, Thrash's works exist in collections, uh, due to him working for the WPA, there are pockets of his work. The largest are here in Philadelphia. The Free Library has an extensive collection of his prints and some drawings.

And the Philadelphia Museum of Art holds a substantial group of prints and drawings. Philadelphia Museum of Art did an exhibition in 2001. Another prop, everybody. This is John Ittmann's catalog. You know, the first and only major publication on Thrash, which is my bible. I, I reach for that all the time.

And that was, uh, uh, that was a joyful thing to do just because John really sunk himself into it. And so there were, you know, there were calls every day and what about this and what about that and, and really digging in and how he made this book out of what to me was very scant information about an artist who, he didn't have any children and his wife died shortly after he passed away.

There were some distant relatives, nieces, nephews on both sides of the family that I've come to know over the years. Um, but there was no cache of material to find other than what was already in institutions. So, um, thank goodness for printmaking, thank goodness for the WPA. I think Thrash might have just slipped between the cracks.

I think he might have, had he not had the four or five years that he had with the WPA to produce the work that he did. I wonder if we would know him. I wonder if he would emerge now. I mean, maybe, but not like, it's hard to imagine, but I kind of think it would not have been the same. Were his editions really small after the WPA?

In many, many cases, there was only one or two known impressions of prints. On the one hand, the, the, the beauty of prints is that there's multiple and they can be in many places and therefore we can know who they are. So in contrast, maybe somebody like Grant Wood or Thomas Hart Benton, where they were published by Associated American Artists and 100 or 250 copies were made of a print.

And so they're, they're distributed widely. They're kind of everywhere. It's easy to know and they become ubiquitous because they turn up and stick in our brains from time to time. We don't really have that with Thrash. There's maybe 10 prints, I'd want to say, where there's enough of them that, you know, I can start to think where I know of eight, nine copies of, of certain prints.

That Sunday Morning one seems to be everywhere. ?Or is it just me paying attention? That's you paying attention, I think. Is it everywhere? Georgia Cotton Crop, I feel like we've had, you know, maybe four or five of those. We have one now. I'm just always completely surprised when something turns up.?

By working with the Free Library of Philadelphia, we were able to include maybe about 10 prints, but two of them are major lithographs, Octoroon and Ebony Joe. Just beautiful, rich, warm, greasy lithos, and those you rarely, rarely see.

I mean, I'm not sure why, but, without the WPA deposit collections, you know, they're prints that I've just never, ever seen outside of captivity, ?so to speak.

So I was very excited to include those because they're, they're rich, powerful images that. And oddly enough, Octoroon and, ? and they're slightly larger scale than what we think of as WPA. They're maybe, they're maybe 14 or 15 inches in length. We did an exhibition in 1989, I want to say, of about 40 works.

And we had a drawing, we had a beautiful ink study for Octoroon. So it's, it's always been fun to link the unique works that come along within these collections that are known and now documented in John's book. ?If I turned up a Dox Thrash in my aunt's attic or whatever, are you the go to? Do people come straight to you or are there other dealers that are handling works by him?

I think on occasion other dealers have things, or sometimes they have things that we've previously sold. I think we're the, we're the people that have done most and most consistently. One of the things that impressed me at the time of the 1989 exhibition was, uh, at that point we were advertising regularly in the New York Times and, and we got phone calls from people in Texas and people from all over the country.

So this is all pre-internet time. But that was another, uh, thing that impressed me deeply that there were people who knew who this was. Uh, he, he's in, in the very important early books by James Porter and Alain Locke. So he had these credentials from early on in his career, but that his, his work entered the sort of collective consciousness of who the important early African American artists are.

Earlier, you mentioned that he was a Master Printer of, of sorts. Did he have a studio that other people came and printed with him at? I don't know that. I think he served in that role in the WPA in Philadelphia. Philadelphia had a stand alone print workshop as part of the WPA, and there weren't very many of those.

Philadelphia, I think, is a real crucible at that point. There's a lot of strong printmaking, and, and the then Print Club was there, so there was a place to show your prints. It was pretty important. In fact, I'm thinking now that I'd like to do another online exhibition that is Philadelphia printmaking.

And I'm not sure the brackets of it, but starting in the 30s. There's an international figure, Joseph Pennell, who's very, very well known. But then by the late 20s or 30s, we have Thrash, we have, Benton Spruance, Robert Riggs, um, and then lots of other folks in between that got caught up, I think, in their success.

I don't know, maybe it was novelty, I'm not really sure. But printmaking seemed like a good idea. And then also Hayter came to Philadelphia. The Print Club sponsored workshops with him. So Atelier 17 has something of an outpost in Philadelphia in the 40s. That's another rich story that I'd like to dig into.

Yeah. Oh, that sounds cool. Yeah. I don't think I have ever thought about the physical manifestation of the WPA workshops. And so when you say that it was stand alone, the other ones were tucked into a community art center or something? Or how did that work? Yeah, I think, I think that's right. I think, well, I think there was a, a stand alone workshop in, in New York.

Gosh, I don't know. There certainly are a lot of New York prints that are WPA. Sure. But I think in Cleveland, it's embedded in something called Karamu House. Oh, okay. Yeah, I'm not sure, but, but I don't think there are many. Even though there are many, many prints, I, I think they were part of art centers.

Was Thrash the director of the Philadelphia WPA shop? I believe a man named Richard Hood was the director. I mean, he was known and made wonderful prints as well. I think the big story coming out of the Philadelphia WPA workshop was Dox Thrash and the carborundum mezzotint, which was a technique that he invented and developed with two other artists, Michael Gallagher and Hugh Mesibov.

Thrash is in the workshop and there's carborundum grit, uh, which is the kind of grit with which sandpaper is made. And it's, it's already in a print workshop because you use that grit to grind down litho stones so that you can ?erase the image that's on there and create another image on top.

And, and that's done by very meticulously and slowly grinding away, sanding off the image. So, Thrash wonders what happens if you take the grit and you grind a copper plate. It doesn't polish the plate. It turns the plate into a mezzotint like texture. In other words, a sandpaper like texture.

So he does this and he inks it and Mesibov says, gee, I think you can, you could burnish out an image in that as you would a mezzotint. And so they start working with it, and, uh, Mesibov is right in there with him, and Gallagher as well, and it becomes something of a sensation. . At the time, the WPA needs some stories, because there were lots of people who did not think that the federal government paying artists to make art was something that was good for the country or fair or something like that.

I'm not sure. Um, but it was created to put artists to work and I don't know that anybody would argue now the benefit of it because we have this huge body of work made at a time when everybody was suffering, when the country was on its knees, the world was on its knees. And out of that came thousands and thousands of prints and hundreds of paintings.

And, and that's a rich document of, of what life was like and what people went through. The WPA issues a press release and writes a paper about this new discovery so they can say, well, see, the WPA is doing important work. We're developing new techniques and so on and so forth. And there are exhibitions that travel around and they're included right away.

It's something of a sensation. It kind of puts them on the map, as it were. Sure, it's propaganda, but. Well, yeah, I guess, but it's still, I mean, there are still artists who are doing, you know, their sort of social satire, social critique stuff within the structures, right? Oh, absolutely.

The other, I think, significant thing about that is, if the prints weren't very good, then people would say, so what? But in fact, the prints are lush and sensuous, and they end up getting something that I think is, not that I don't like mezzotints, but there's a richness to it that's not like a mezzotint. It's, it's kind of smoky and soft. And when you look up close, you don't have the evidence of the rocking tool with which you would make a conventional mezzotint. It's, it's all very kind of soft and, and velvety and, uh, and quite lush. And then also pretty much every artist in the Philadelphia workshop takes a crack at it.

And, and, and so, this is the new thing. And so after Thrash, uh, Michael Gallagher makes the next most significant body. He embraces it and makes really, really wonderful prints with the technique. Hugh Mesibov does as well, uh, and then some others probably, gosh, I don't know. I should go back and look.

But there are a lot. In fact, there was, I want to say there was a woman at Baltimore who did a paper on it. Oh, Cindy Bruckner. Oh yeah, Cindy, of course. Yeah. She did an article on, on the the carborundum mezzotint. Right. That makes sense. And, and, and, and lists maybe, gosh, I don't know, 40 or 50 artists that that also worked in the technique. Yeah, Cindy Buckner was at the museum when I first started there, um, when I was not in the prints department yet. And she did this great WPA show drawn from the deposit of works at the museum. And there's a nice catalog for it. And then I, I have not read, I'm sorry, Cindy, haven't read your carborundum mezzotint one, but that makes total sense.

Yeah. I didn't know there was a catalog. Yeah. I have multiple copies. I'll send you one. But, I think she also wrote an article that was in Print Quarterly or something like that. Yeah. Anyway, this story is, is there. And I think I don't dislike the idea of working with kind of an underdog. So getting back to this, like what, you know, why isn't this artist better known?

In my own opinion, I think what he makes is as good as anything made in that era. As time goes on, I think more and more museums that have, that want to have a strong American print collection feel that, that he's an important story and usually endeavors to include his work in their collection and exhibitions.

Right. Well, I mean, everybody's trying to catch up in, in their representation of Black artists in the collections. And, and Dox Thrash is, you know, he's pretty early, really, in the story, so that's always a. Yeah, I, I guess you could say he, he's, I mean, certainly Henry Tanner made some etchings, a handful of etchings.

But he's the first African American artist that, that is identified as a printmaker. And again, this term master printmaker. He embraces it and does a lot with it. Make, makes a significant body of work of over 400 print designs. 400? That's a lot. I think so. No, sorry, wrong.

Okay. 200. Okay. Well, 200 is still not nothing. No, no. I mean, we know artists that it takes 10 years to, you know, produce three. Yeah, that's true. Um, I'm gonna bring up 400, but no, 200. And, and, you know, interesting, a lot of effort and, and time put into putting the book together. And, and since then, I want to say that about 10 different print designs have emerged that we didn't know about, that we didn't find in time to do this.

Well, that's always the fun of the underdog artist, right? Who's hiding what in there? Yes, absolutely. I'm thinking of a print that we have called One Horse Farmer, ?and when John did the book, he found Thrash's widow gave some plates to the Smithsonian American History Museum maybe around 1970. And so these plates were there, but they didn't, she didn't have prints. So in the book, there's, there's probably ?three or four cases where he's using a photograph of the plate to signify a design.

Oh my gosh. And then maybe about four or five years ago, I mean not that long ago, an impression emerged. So I can't tell you how precious that feels to have something that you know, we were looking for 20 years ago. Right. You know, time heals all wounds. No, no. Time reveals all prints. Maybe. Yeah, maybe.

Maybe. I hope so. I hope so. Yeah, I think people probably don't know that Helena Wright is the curator at the Smithsonian American History Museum. And they have a rather substantial collection of printing plates and printing industry things, right? I don't know how big their print collection is necessarily, do you?

No idea. Yeah, I don't know. You know, again, somebody convinced Thrash's widow that it would be good for her to give those things there. And I wonder, what do they do with them? I know what they do with them, Ron. They put them in a drawer for safekeeping. Exactly my point. They're not doing anything with them.

Yeah. Well, I mean, they probably have some printing stuff out. I mean, haven't been there in ages, but, um, yeah, no, I mean, you know, there it's for, it's for posterity. Yes. That's everybody's complaint about giving things to museums. So they're just going to go in a drawer, but you know, if they weren't sitting in that drawer, you wouldn't have any idea where the thing was, right.

No, I, I, I, I get the whole save it theory thing. I know, I'm preaching to the choir. But, you know, the. Yes, I know. I wish, I mean, we love showing plates. I would have loved to. And, and the constantly moving target of when this show will open, I would have loved to have gotten the plate for One Horse Farmer to show a plate with, because I've never been able to do that. We do it with Hayter a lot. Hayter loved his plates and didn't cancel them. And, and, and they're amazing. They're beautiful objects. So, um, thank goodness he didn't think he needed to cancel them, but, you know, due to the pandemic, et cetera, it was, it was complicated.

We didn't actually get to borrow a plate. Not to pick on the Smithsonian American History Museum. Uh, I guess what I was getting at was, would they be more relevant in the Smithsonian American Art Museum? It's a good question. And then it becomes, for the Smithsonian, that becomes a question of where you put your resources and where that makes the most sense.

Sure. But to your point about Hayter, do you consider the plates to be works of art or to be the, the, functionality of getting the thing printed, you know? In Hayter's case, both. Right, of course. But for Helena, I think it's, it's about recording the industry and, you know, all of the ins and outs of how you Right?

Sure. It's a hard call. Most museums won't even take the plates, right? Like, I always wanted to collect the plates, but not a lot of museums do. Oh, I think they do. And I think we've been successful selling the plates because printmaking is infinitely teachable because you have the tool, in the case of the plate, and in the case of Hayter, you have recorded state proofs along the way.

I find that museums think, well, wow, we can actually show people that idea. Like, well, here it is. Here's the beautiful example of this artist's work. I think they like to be able to say, well, here are the four or five steps that it took to get here and by showing the different state proofs, we can indicate his thinking process and how the, in Hayter's case, they're, the first states are often just sketchy lines, beautiful, engraved, beautiful, elegant, sketchy lines.

In the second state, he engraves further and develops an image, and by the third state he's adding soft ground textures, and by the fourth or the fifth state, he's adding color. In many cases, after 1946, there's, there's color added. So, you know, I think we, you know, we enjoy that, and we've done that.

We've sold plates and states to museums because they like this ability to share a process and share evidence of the artist's approach to making something. Yeah, no, I agree with you. And with Hayter, and in that time period, it becomes even more important because, you know, not everything is in the plate because he's adding color on top of the plate in essence.

So that it's even more confusing to look at the print and try and figure out how it's been made. And even if you have the copper plate next to it, you're like, wait, where's the, you know, it's so we've never had. I've never seen the screens for Cinq personnages, ?for instance, you know, I don't know if those exist.

Probably not. I don't. I think they probably don't exist. No, I'm sure they didn't. They probably washed them out and used them for something else, you know, right? ?Right. They were tools. Right. Yeah. Why, why preserve them? Right. They'd be pretty decrepit by now. Exactly. But the copper plates, when I was at the museum, I got contacted by the estate of Ian Hugo and Joann Moser and I took a trip up to this person's house who had all of these things, including scads of copper plates. And she was telling us that, that Ian Hugo and Anais Nin, his wife, had created in their apartment, a Japanese screen, folding screen, but that the, the bulk of the, the you know, what would be paper in some other screen were actually copper plates hung decoratively as the room divider.

And I just thought, Oh God, I'd kill for a picture of that. I know. Yeah. Yeah. That must've been so heavy. Well, that too, that too. But just imagine. That's a shame that doesn't exist. I know. I know. Yeah. Anyway. It's a pity there's not at least a photograph. Maybe Christina will turn one up one day. Yeah, yeah, yeah. We'd love that.

But you're right about what you're saying that once color becomes such a big component, that's magic that happens between the ink. I mean, the inking almost becomes becomes part of the plate. Right. He's, he's using viscosity to resist and, it's this kind of magic, this alchemy of, of making ink do more than just transfer onto piece of paper.

Yeah, exactly. Yeah. When we were working on the, the big Hayter show at the museum, Ben came up with this brilliant system, which was in the descriptor line that you would include what's in the plate and what's on the plate. So you would have that it was etching with soft ground and whatever else.

And then it was the inking, how the inking went. So it was inking, you know, surface roll or soft roller or however we said it. So that there were two elements to it. It was not just what's, what got put into the plate itself, but also how the inking went, which was confusing and needed clarification.

Thankfully they did that in the catalogue raisonne? Uh, Hayter's widow did that. It does list mostly. It's not always mostly, but, uh, um, but you're, you're right. Ben was wise to take that out of that and say, well, let's, you know, let's tell people, let's not make them go look for it. Yeah, no, it was a great system.

So when you started working with Margo Dolan, who of the name of your gallery, she has had a long relationship with Hayter and with Hayter's widow, Desiree, who's lovely. But you, you never met Hayter before he died. No, regrettably. You were this close. I was so close. I was so close to, uh, no, Margo Dolan and her husband, Peter Maxwell, who own the gallery. Um, I think Margo, and I need to ask her this, actually, because I'm, I'm speculating somewhat, got to know Hayter through the Print Club of Philadelphia. Margo was director of the Print Club in the mid 70s. And I think Hayter probably continued to submit things to shows. So I think she became aware of him then.

Margo also got very close to Sylvan Cole, Director of, long time director, and, you know, really kind of king of the print world. I think of him as an impresario, you know. Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. Uh, I did know him, I knew him well, and uh, yeah, he was, what a great guy, and he and Margo were very close.

Uh, Margo got to know him because, in organizing exhibitions for the Print Club, she would borrow from Associated American Artists, and, and then, she did so well selling work that the 501c3 status of the Print Club was threatened. They said, well, hold on, you know, you're selling stuff, you're a gallery, you're a for profit.

And, and the Print Club didn't want to lose their 501c3 status. So, um, Margo and Sylvan cooked up this idea to open a branch of Associated American Artists in Philadelphia. And Margo did that for maybe six or so years, I want to say. They cooked up a scheme where the second floor of the Print Club would become Associated American Artists, and the Print Club could still operate as a non profit on the first floor.

And so that went on, and then Associated American Artists was sold in the early 80s. I think probably not for the right reasons. And, the people that bought it were, were hard on Sylvan and then, and, you know, audits and all this sort of stuff. Oh, well, yeah. And for, you know, forcing him out. So that's when he opened Sylvan Cole Gallery.

And then Margo could see that she was next. So she preemptively closed Associated American Artists and, and bought a chunk of inventory and then created Dolan Maxwell. Gotcha. And was Peter ever really involved in the gallery? Uh, deeply so. Uh, Peter was a designer, so, uh, he was kind of the in house brand expert and, and designer and designed, I don't know how many catalogs for exhibitions, designed all the signage, all the announcements, and when I started, he and I would hang all the shows.

And he devised in the gallery, it was a really beautiful 19th century building with a beautiful white terracotta facade on it, it still exists, and uh, our gallery was on the third floor and it had these beautiful, uh, molded ceilings that they had restored. And he devised a system of I think they were six foot by eight foot walls.

And he invented this kind of spring system. So two of us could push these walls around and lock them in with this spring system into the ceiling. So every exhibition had a completely unique layout. And we had maybe, I want to say we had six of these walls. So sometimes they got ganged up and made a long wall.

And sometimes he made little coves. So yeah, he was very much part of designing all the ads, designing the the look of the gallery and I learned so much from him. I feel like I use, I use what I know from him every day. Oh, nice. Yeah, by the time I met him, I'm not even sure I met him, honestly, because he was, he was ailing at that point, the first time I was at the gallery, but he was an architect also and designed the space that your office is in now.

Yeah, he wasn't trained as an architect. Oh, funny. He just, he just, he had a real designer's mind and, and, and could think that way. He had an innate ability to solve problems and thought it all through. And if it meant redoing something, he redid it. So he designed the beautiful carriage house that we're in.

In the nineties, Dolan and Maxwell created a artist residency program in Ireland called the Ballinglen Arts Foundation. And after opening their own gallery and expanding it and it get getting very big, and then deciding to retrench and scale back, he wanted to spend more time in Ireland and then they dreamed up this foundation idea ?and residency program, which has become shockingly successful. And we're just constantly amazed that it kind of runs forward at a speed. And about 3 years ago, we opened a museum. We were able to secure funding. It's in a very remote part of Ireland in County Mayo, a very beautiful village half a mile from the North Atlantic with ?300 foot cliffs and then beaches and, uh, just beautiful farming communities is all it is really. And he designed all those buildings as well. Oh, but they were purpose built? Yes. Oh, okay. All right. Yes. In my mind, I assume they had converted, you know, a farmhouse or something.

Actually, there was an existing little vernacular storefront. The original gallery was a courthouse, but, you wouldn't know. It just feels like a little storefront space. So that was existing, but the rest of it, he created a series of rooms and, and second floor sky-lit studios and, and very elegant, very beautiful, beautiful, warm, interesting building.

So, you must visit sometime. That would be nice. Can you explain for folks how the residency program works and how you go about getting in? There, I think we're about to reopen applications. If you want to do a paid workshop, there's about There's 15 to 20 week long workshops that happen there throughout the spring into the fall.

Uh, the fellowship program is separate. It's by invitation or by application. And I, I believe, I should have checked this, uh, that the website now has an ongoing open application process. Uh, there are four studios, so it's very small. It's got a nice intimate quality to it. You're encouraged to bring family, so it's not a, it's not a colony thing where you go to be away from the world.

You can take your family with or your partner. There are people who have gone when they have a sabbatical and they've stayed for six months and put their kids in the local school and. There's been some really really nice stories about that. But we we had shut off the application program because of the pandemic. We had, you know, people were unable to fulfill the, the residencies and we had a backlog.

So I think we're finally working through that where there will now be an open application process again. Is there a print studio there or is it really for painting sort of stuff? Uh, there is also a print studio. It's not big. There is no acid setup. Dolan and Maxwell decided from early on that they would only do direct process stuff that we didn't want to get into dealing with the chemistry of, of etching.

But you can dry point and relief print to your heart's content. And who's teaching all of these workshops? The workshops are all run by people who were fellows. Ah. So it's somebody who kind of already knows. Because you and Margo, you're not there. No. I mean, it's running itself. Regrettably not. Sorry. No, we have a director, Una Forde, who's been with us

gosh, maybe 20 years. She's, she's a force of nature. She's amazing. And then there are some staff around, around Una. One of the other functions is it, there's a whole schools program. So the elementary and secondary schools all come in and do workshops. Museum visits now and workshops in the print studio, which is, um, charming, and Nuala Clark runs that program.

Nuala very fine artist herself. Phil [Sanders] went over and did a workshop. I'm trying to think who else you might know. Yeah. Didn't Shelley Thorstensen do one? Did I dream that? Shelley Thorstensen did a workshop? You're absolutely right. Alice Austin is a bookmaker. She's done workshops. Two very distinguished Philadelphia painters, Jeff Reed and Randall Exxon do painting workshops. They're the only two week workshop, I think. So, yeah, it goes and goes. That's amazing. It is amazing. Yeah. I mean, it's amazing to me. Let's set up a thing and some other continent, it was really Peter Maxwell's idea.

He had been going to Ireland. He met Margo and when they got together, he took her to Ireland and he visited the Southwest. He visited Tipperary, the more tourist based western part, west coast part of Ireland. Just as he would talk to people, somebody said, well, you know, if you want to see old Ireland, you should go up to Mayo, go to, go to these places that nobody goes to.

And, and Mayo is on the west coast, northwest between Donegal, which is a tiny little place and then Galway on the west coast. The coast is rugged and beautiful and dramatic and the light changes all the time because the whole atmosphere rolls off the North Atlantic.

And the way the geography is, the coast there actually faces due north, and there's the sea stack, there's something called Downpatrick Head. It was a peninsula that the ocean gradually wore away and created these tunnels underneath the land and then there was a land bridge and the land bridge fell in, I used to know the date, 1358.

Oh gosh, wow. And a long time ago. It's like a tall skinny island that sits right off of the, right off of the coast. And apparently if a helicopter, you have to get there by helicopter to land on it, apparently there is still residual stone walls and evidence of, like, it had been farmed.

There's another important archaeological site there called Céide Fields. It was a site that was excavated over the past, uh, 40 odd years, I want to say, where an archaeologist figured out that, I mean, the area is all covered with blanket bog. He figured out that if you drove poles down in the bog, You know, one pole would go down 12 feet, the next one would go down 11 feet, and then 9 feet, 8 feet, and he figured out, well, those were, those were the stone walls are that are buried, and so they excavated out and discovered this whole 5, 000 year old farming community.

That, which is basically the same as what exists there now. So, so there's this deep sense of people have been living there and existing there longer than the pyramids in Egypt, doing this, this same kind of farming work and living in these sometimes really, you know, brutal conditions.

One last question. Who, who's your, um, favorite artists that you carry? I mean, I know you can't play favorites, but like, if you could buy something today and bring it home, what would you bring home?

I mean, things must come in and you're like, Oh, I love that. I want to bring it home. I mean, I still remember my, like, what I would bring home from the National Gallery was a John Ruskin ?watercolor. Oh, nice. Nice. It's difficult because I, I feel like if I think about it, I don't want something it ends up being that I, I like too much.

?Oh, no, I couldn't, I couldn't possibly, you know, I will say I'm looking at that and behind me is this great Hayter painting. Exactly. I did, I did, I did bring that home. Yeah. And I love it. And I spend time with it all. It's a late 80s painting. I think it's 1984 and uh, I think it has all the energy of, of even his kind of 30s and 40s prints.

Um, so I, I'm going to say it's a toss up between a Dox Thrash and a and a Hayter. And a Hayter. Okay. How's that? I'm right with you. And the two artists that I, I feel like, well, Hayter had this huge reach and this huge web of influence that's global. And then Thrash for somebody who I think was probably more humble and I feel like his work is all very, very personal.

And he's also somebody that I, I remain very curious about and feel like I'm nourished by looking at his work. Ah. That's something that's important to me. It's like, you know, what can I get? Can I look at it and think about it and then find myself thinking about it in another way? And you can come up with a list of aspects about a work and works that kind of expand in my head. That's, that's still thrilling. Yeah. Well, we've never talked about works nourishing people on the pod, which, um, I, I love that term, but I also wonder if that's a function of you being an artist yourself. That kind of engagement, it's probably more expansive.

I mean, we started out saying that I feel like my job as a dealer or a gallerist is, is to get eyeballs on the art. And, and only at the last New York print fair, um, a very nice, very middle class looking woman came along and we showed her something. And she said, I really liked that, but you know, can, can you tell me, is this going to be a good investment of my money?

And I took a lot of deep breaths and said, uh, no, I'm not gonna tell you that. Like, what do you, why, what do you want? If, If you think you're gonna make money, please do not buy art. And I, and I tried to steer the conversation around to, you know, you should look at many, many things and buy something at the low end of your, your comfort zone and take it home and live with it and see if you're nourished by it. See if you, and, and there's a good chance that if you keep looking and if you keep, um, spending time engaged with looking at art, you're going to outgrow that. You're going to find something that, that nourishes you better or, or, or brings you up to a whole other level of, of intimacy with a work and, and engagement.

Yeah. Um, you know, that's what this is about. Not your money. Look, if your money is so important, do me a favor, keep it. Don't, don't put that false expectation on a work of art. It's so not fair. I don't think the really good artists think, oh yeah, you know, I'm gonna make a lot of money because what I made is just so good.

I mean, I think there are, and I'm not very interested in that, but to me it has a very different purpose than some kind of commercial. And sometimes people, there are people that make a lot of money. I mean, I worry a little bit that the market right now, in fact I just read something recently about, people are saying there aren't young people coming into the art market, or they're coming in and they think it's a financial game.

They're gaming, they're betting that they can get something and flip it. And I had an experience recently where sold a painting, perfectly nice painting, and sold it through an advisor within 18 months, you know, the guy wanted to flip it. And I just thought, oh, I'm not interested.

No, but that also means that we have failed in, in educating people in how to look, right? This is our call to call to action. Keep doing it. Keep teaching. But I also wonder if we're not, your question, like, what would I take home? And my response to this is, how am I nourished by something? To me, that's what I'm looking for, not any of those things. So, how do we get people to look at things and think about their own engagement with it. You know, what do you see? What do you, why does this, you know, why, why do millions and millions of people agree that, that Vermeer's paintings are these things to die for, you know?

And, and he only made 36 of them or something like that. Now 35. Oh, really? Yeah, one got downgraded. Yeah. Oh, I didn't, I didn't see that. I missed that. Yeah. You know, what, what, what is it about them? I mean, I think we know what it is. There's a sense of intimacy and they're beautifully made and, and, um, they're, they're perfect. When they're good, they're really just these perfect things. And, and he did it consistently. All the other artists do whatever they do. As well as, or less well as than others. I think so many people come at art and they have no idea why, or they have no idea what they like, and then they expect that there's some magic that is going to, you know, Get them there.

I think the only way to really do it is just kind of look and look and look at many many things until you figure out what you connect with on a visceral level. Right. Well, and I think, I feel like there's, there's a sort of a Y in the road, a fork in the road where there's a column of art that's just, just plain beautiful or not beautiful, but it's essence is about its beauty and its effect on you visually.

And then there's, you know, the things that have meaning that might take longer to suss out. And I don't know, I feel like there's, there's such different things and feelings when you're processing that kind of stuff. It's kind of funny. Like these parallel types of objects, so funny. And then if there's one that does both, you know, then you're singing.

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. Anyway, sorry to bring up the person who wanted to know whether it was a good investment. We talk about that all the time. I'm like, don't buy it cause you think it's going to make you money buy it cause you love it. Jesus. And then you'll, then you'll always at least love it or you, or you can love it until you no longer love it.

That's okay too. That's right. You can upgrade, you can trade it in for something better. Yeah, yeah, one of the nicest things somebody said to me was, this lady came in and she was looking at, probably it was Hayter. We were talking and looking at things and all of a sudden she caught herself and she said, You know, I just realized that if you told me I was going to think about buying one of these 20 years ago, I would have said you were crazy.

I, I, I would not have understood this. And, and she said, and it makes me think about, she said, I also love music. And I think she was a, you know, she was a big supporter of the orchestra or the opera perhaps. But she said, it reminds me of how 20 years ago I liked a certain kind of music. And now, and now I think that kind of music is, you know, it was twee and I've outgrown it.

So this idea that you're engaged and you're, you're going to outgrow and you're going to develop and get deeper into the nuance of what art can be. Right. And that's worth chasing. That's a worthwhile pursuit. Yeah. Is there anything we haven't said that we want to say before we sign off?

I guess maybe I'll say, one of the interesting things that has come up really since we planned this current exhibition is, a group of preservationists from the University of Pennsylvania took it upon themselves to, uh, it was really an act of protest because there was a neighborhood in Philadelphia where, where Thrash owned a house. It was then 24th and Columbia. Now it's 24th and Cecil B. Moore. Uh, but the house existed and there was a mural painted on the side of it, which probably about five years ago, all of a sudden the paint, somebody had taken black paint and erased the mural. And, and people, yeah, people got upset.

And, um, it was a neighborhood that's now called Sharswood because the redevelopment authority, or the housing agency in Philadelphia had decided that they were going to go into this somewhat blighted area and basically bulldoze it and build much more suburban kind of housing. And these preservationists created something called the Dox Thrash House Project, with the idea of, they created a tour of the neighborhood saying, you know, there, there's a lot of history and a lot of African American history in this neighborhood that didn't, you know, it wasn't right to bulldoze that and, and bury it. And miraculously, they focused on the Dox Thrash house, which was actually bought by a developer, and it is going to be preserved, but they are continuing to do programming with, uh, a few doors down, there's a public library, and they're doing all kinds of printmaking programming, uh, in the name of Dox Thrash, which is very gratifying and very exciting. And another collection that evolved, there was a woman who owned the studio, the building where Thrash had his studio, shared a studio with another artist named Sam Brown and, uh, she ended up with a substantial collection of drawings, you know, some of them this big, many of them this big, and, uh, for a time she worked with us, John Ittmann somehow tracked her down, and, and then she said, what am I going to do with all this stuff?

She worked with us for a while. We sold some things for her. Uh, and then at the end of her life, she still had a substantial group of things intact and she decided to create a foundation with the idea that it would become an educational collection to be developed as, as a specific entity of works that we've exhibited and we borrowed about 14 for the current exhibition and that's called the Macintosh Rollins Foundation.

Yeah. It does feel like that after all this time, uh, the idea of Dox Thrash as an entity, there are growing, interest in taking him further or, or, or greater recognition of him as sort of a cultural entity and signifier. Oh, that's great. And the foundation holding the drawings, they're being held where?

Well, a lot of them are stored in my studio, so it's still, it's very grassroots at this point. But we had done an exhibition of, of the collection at the Fleischer Art Memorial last fall as part of their 125th anniversary, I think it was. They wanted to do something and Dox Thrash was the artist. It used to be known as the Graphic Sketch Club. And he made prints there with Earl Horter in the 30s.

Oh. So it was, it was kind of a nice homecoming. That's great. People may not know what a historic place Philadelphia is in terms of prints and printmaking. Like isn't the Print Club, the oldest in the, did I dream that? No, it started in 1915. It's, it's 110 years old. It's old, I think it is the oldest.

Yeah. Yeah, yeah. And, and, 30 years ago, they, they changed the name from the Philadelphia Print Club to the Philadelphia Print Center. Because at the time they were thinking, well, we're not a club per se, and, and it was never, it was sort of a club. It was, it was really a nonprofit gallery that did workshops, but also, um, did a lot of exhibitions and did really important annual shows about prints very early on.

It had a societal component to it. The openings were afternoon teas. Oh. And, if you were socially inclined, you, you would join and you would earn the position of hosting the teas. There's a really wonderful history there. Nice. And then by the 70s, it had become kind of a party spot where all the cool kids would show up for their openings.

Um, so that has a huge history that, um, oh, gosh, I was on the board I remember we celebrated the 90th anniversary. So that's how long ago that is. But because of that, and because of all the art schools and places like Fleischer, there's a real rich nucleus of printmaking that happened here and produced among the finest artists, I would say.

Benton Spruance and Dox Thrash leap to mind. There you go. Yes. Nice. I will do my very best to get it up before the show closes at the African American Museum. I will do my best. Thank you. I, I, I think it's a good thing to do.

And, um, and we talked about many things, but thank you. I appreciate it. I mean, and to all you people listening out there, if you have a project and you want to get it on the pod, know that there is lead time. You have to think about it before the show goes up. Get in touch. Yeah. Well, it's obviously a, a, uh, a passion of yours that comes through.

Yeah. Well, thank you. Yeah. I mean, it's, and I'm doing my part for the ecosystem as it were, this is what I can do best. Give everybody a platform. Yeah. Cool. Yeah. Excellent. Excellent. All right. Well, thank you for doing it, Ron. It's been great talking to you. You're always, you're always fun to talk to.

Likewise. Yeah. ?

Thank you for listening to this episode of Platemark with me, Ann Shafer.

I hope you enjoyed our episode with Ron Rumford and learning about the life of Dox Trash. And also we got into Bob Blackburn and of course Hayter. So no surprise there.

I hope that you all will run over to the African-American Museum in Philadelphia to take in the exhibition Imprint: Dox Thrash, Black Life and American Culture, which is on view until August 4th, 2024.

Thank you to Ron for being a wonderful guest, he's always a delight to talk to. And also the other thank yous that I always have to do are to Michael Diamond for the use of his original music and to Dan Fury for his help with sound editing because good Lord.

I'm terrible at it. Also. I forgot to thank Scip Barnhart and Lee Turner for sending over sounds from their studios for my soundscape at the top and bottom of the pod.

The images we talk about are over on the show notes at platemarkpodcast.com.

Also over there, you'll find the support and donate button, click it and help me keep the lights on. Cause, you know, it's just me.

Yeah. Got it. You know? If I can't monetize this thing, it's not going to, I can't keep it up forever. So. So I've got to get myself paid for this. All right. I think that's it. If you've listened to this far, congratulations. You are a devoted listener and I appreciate it. All right. We'll see you next time.